Now that I’ve been stuck at home, I’ve been watching a lot more YouTube videos, and I’ve noticed something peculiar: people clapping their hands before beginning to film, like so. And so, in the enterprising engineering spirit, I began to wonder why.

Similar to movie clapperboards, clapping is a very low-tech, easy way to make videos cleaner and crisper. Most commonly, this helps synchronize video and audio in post-processing. In order to achieve better sound quality, videographers will often use microphones separate from their video cameras: think boom mics in movies, or hidden clip mics for YouTube vloggers. Since a single clap creates a big spike in the audio spectrum that is easily synced with the video of someone clapping, it’s helpful to clap at the start of a video to connect the two. Particularly if you’re using multiple cameras, this allows you to move seamlessly between shots while keeping the same audio track.

That being said, there is another interesting way the clap can be used to edit audio. By having each person clap at the beginning of their video, in post, you could edit the audio as if they were all in the same room. It all has to do with the impulse response.

First, some signals and system theory. Feel free to skip this section if you already understand transfer functions, the Fourier transform, and the impulse response.

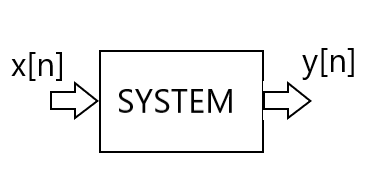

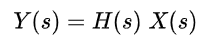

We call a system something that we give an input x[n] to, the system does something to it, and gives us an output y[n]. I’ll focus here on the discrete case, because audio is sampled - that’s what the [n] means, each integer n indexes a different sample - but your input/output could also be a continuous function (usually of time). I’m also neglecting quantization, so I’ll use discrete/digital interchangeably.

A system can be described by its transfer function, but to understand that we have to think about domains. We usually think in the time domain, because the output evolves as n gets larger with time. However, we can also think of this in the frequency domain, where we analyze the signal with respect to frequency instead of time. Although it can be harder to visualize at first, understand that each value in the frequency domain is a coefficient of that frequency - the larger the coefficient, the more that frequency contributes to the output. One cool property of the transform domain is that convolution in the time domain becomes multiplication in the frequency domain, so lots of math gets easier.

Sample transfer function for a system in the Laplace domain (variable s). Y(s) is the output, X(s) is the input, and H(s) is the transfer function relating the two.

How do we get to the transform domain? The Fourier transform takes us from time to frequency, and the inverse Fourier transform from the frequency domain to time.1

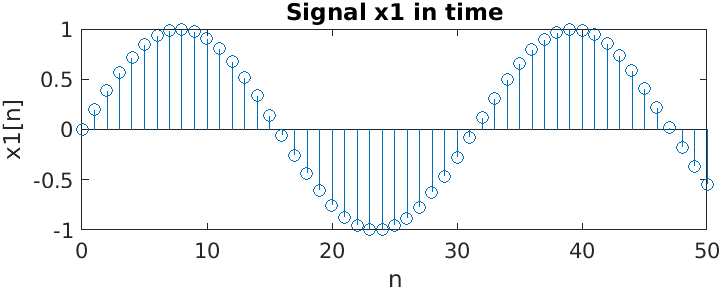

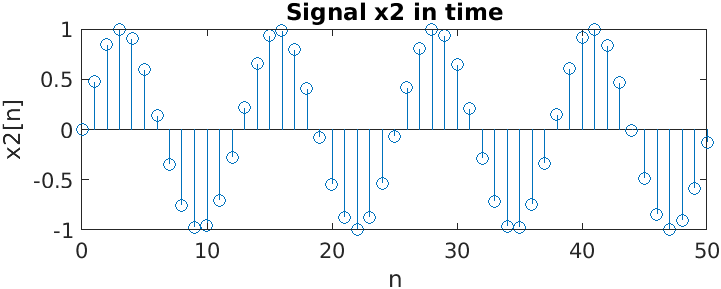

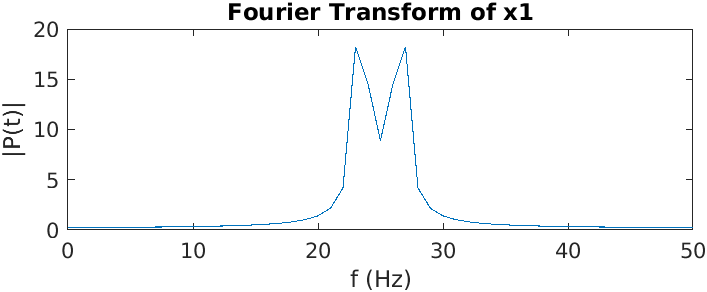

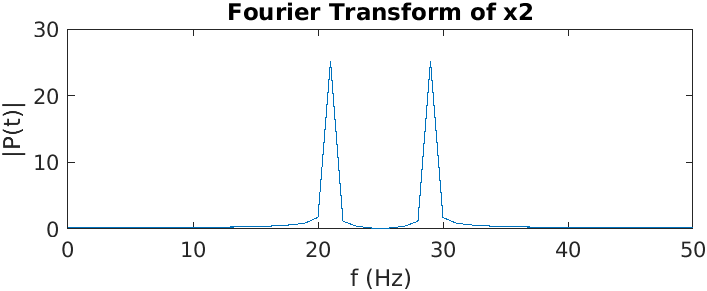

Here we have a two sine waves and their Fourier transforms. Notice that the frequency of the second one is higher than that of the first one, and its second peak frequency is higher than that of the first signal.2

Once we have this frequency-domain representation, we can describe the system as Y[w] = H[w]*X[w], where H[w] is the transfer function, a function of the frequency, w. We can’t have a transfer function in the time domain because the system is described with difference equations, so you can’t simply multiply the input by a function of time to get the output.

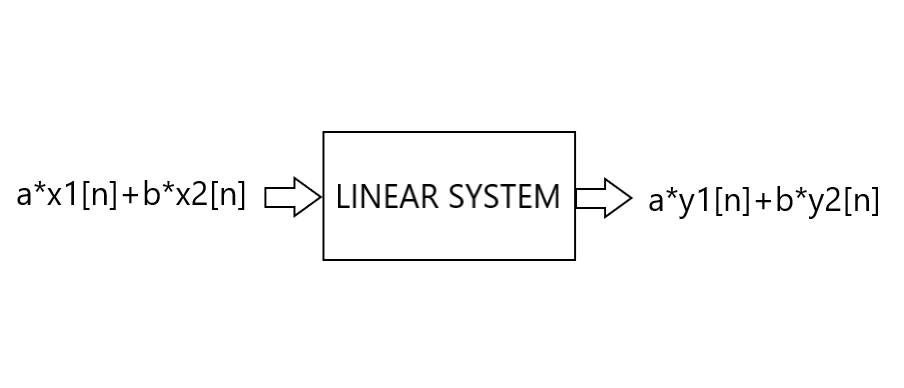

A few properties of systems in general: they’re linear if you can scale and add multiple inputs and the associated outputs are scaled and added in the same way. That is, if you input a*x1[n]+b*x2[n], you’ll get out a*y1[n]+b*y2[n], as in the graphic below.

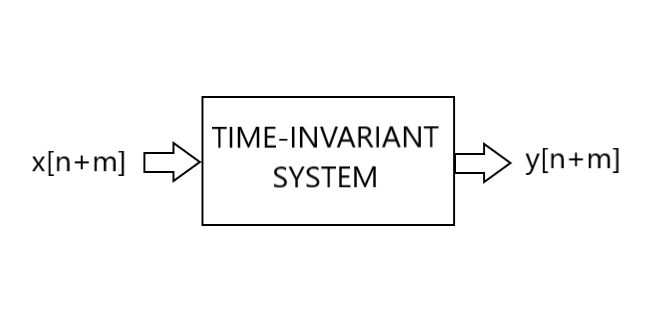

Systems are time-invariant if you can delay the input and it delays the output by the same amount. Inputting x[n+m], you get the output y[n+m].

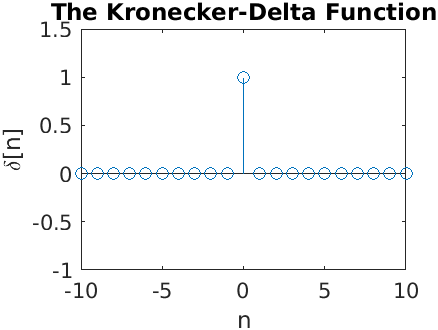

One of the main properties of a system is its impulse response - what happens if you input the delta function (which returns the value 1 for input 0 and 0 for all other values)? We call this output h[n].

This is the Kronecker-Delta function. From what I hear, Kronecker was a cool guy.

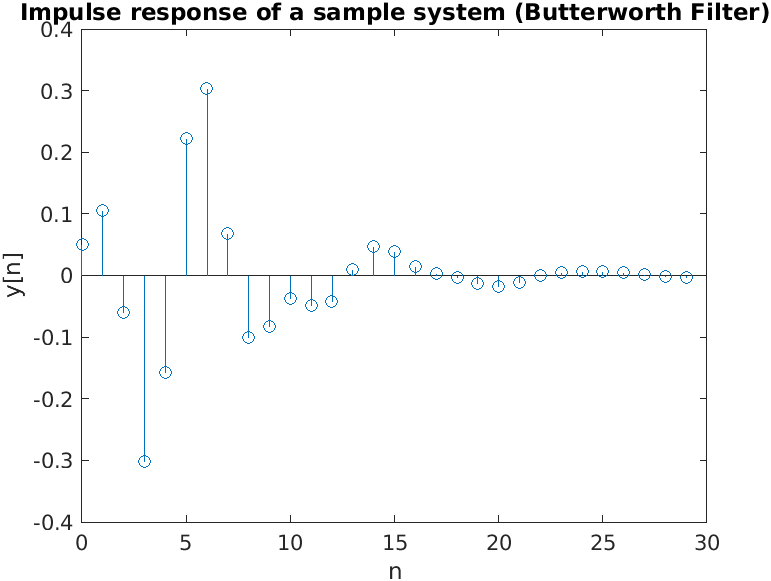

Here’s a sample impulse response for a Butterworth filter. An impulse response can basically be anything!

If a system is both linear and time-invariant (LTI), it has some really cool properties and lots of math becomes easier. This is why we often approximate systems as linear. One fundamental property of an LTI system is that its impulse response is the equivalent of the transfer function in the time domain, which makes the system far easier to study.

Now that we know what an LTI system is, why can we model a room as one? And why is it useful?

When you’re inside a room, sound bounces off walls and other objects when travelling from the source to the receiver, which creates echo and reverberation unique to that room that’s picked up by the receiver. Assuming you don’t live in the Harry Potter universe and that your furnishings don’t change, we can say that the room is a linear time-invariant system. And since the received sound is unique to the room you’re in because of the placement of objects, this system is unique to your room3. And so the impulse response is the intrinsic “sound” of the room.

So we’ve approximated the room as an LTI system, but where do we get the impulse response from? Any sudden and loud sound - a stomp, popping a balloon, or a clap - can be approximated as an impulse because of its amplitude and narrow width, and it’s probably the closest we’ll get to an impulse in the real world. Out of these options, the clap is easiest and offers the added benefit of synchronizing audio and video.

So you use your clap to isolate the impulse response of your clip, and save it. Now what?

If we want to make everyone sound as if they are in the same room, we can remove the unique impulse responses of each individual room, and apply the same impulse response to all clips.4

Remember that convolution in the time domain is multiplication in the frequency domain, and that the impulse response in time is the transfer function in frequency. Once you’ve obtained the impulse response of a clip, calculate its Fourier transform. Transform the recording into the frequency domain as well, and you can divide out the transfer function to simply get speech. Most audio post-processing mediums have tools that can do this for you, and this is essentially how they work.5

Now that you have just speech, still in the frequency domain, multiply it by the transfer function in frequency of the universal room - now perform an inverse Fourier transform, and you have the filtered audio back in the time domain.

Repeat this process for each of n clips, then synchronize them with the clap. Everyone is in sync and in the same room now!

If you found this concept really interesting and want to read more, I found this paper really interesting as it relates to acoustics and the impulse response for measuring acoustics. (Surprisingly, it suggests pistol shots as an alternative to handclapping because of the intensity!)

-

If you’re interested in how I generated these graphs, I published the MATLAB code as a gist ↩

-

The fact there are two peaks is known as foldover or Nyquist frequency. Topic for another time. ↩

-

That’s one way of hanging out with your friends in quarantine, I guess? ↩

-

No doubt they’re actually more complicated and cost more money, but the underlying principle is there. ↩

Comments